Elliott Imhoff

I'm a computer vision engineer for Sentera - an agricultural drone company. I write image processing algorithms to analyze farmland.

This Definitely Will Go Viral

Published Mar 19, 2020

You think a blog post about linear regression can go viral? (Sorry if that word triggers anyone). I sure think it can. What else does everyone IN THE WORLD have to do all day than scroll through the internet and find random golden turds. Like this blog. So to entertain all you socially distanced, caged up, longing for the touch of literally ANY OTHER PERSON people, let me reach across the nethers of the internet and caress you with some math. I can’t promise this blog post is coronavirus free, but trust me - it’ll be worth the risk. The other day at work I ended up looking at line fitting in a new way that COMPLETELY BLEW MY MIND. I GUARANTEE YOU WILL NEVER LOOK AT THE WORLD THE SAME WAY AGAIN!!!

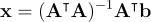

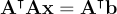

We all know the classic least squares linear regression formula from first grade:

I know it’s hard to remember derivations from so long ago, so I’ll quickly give a little refresher on where this formula comes from. It’ll provide us some good context to build off later WHEN I TOTALLY BLOW THE LID OFF YOUR BRAIN BOX!!!!! I LOVE YOU MY SWEET BEAUTIFUL READER!!! KEEP READING!!!

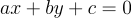

We start with the equation for a line:

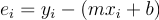

In linear regression, given a bunch of points, we want to estimate the “best fitting” line through the data. In least squares, the “best fitting” line is the one that minimizes the squared error for each data point to this line (hence the name least squares). To put this into a nice math-y formula, the error for a single point  is given by

is given by

,

,

and we define the least squares problem as

Choose  and

and  s.t.

s.t.  is as small as possible

is as small as possible

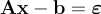

Let’s now write this formula in matrix notation to make it a little easier to work with.

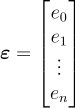

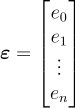

Say  is a vector representing

is a vector representing  for the linear equation we are trying to fit. We can neatly stack every point

for the linear equation we are trying to fit. We can neatly stack every point  into matrix form and represent all their errors at once using:

into matrix form and represent all their errors at once using:

, where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

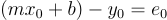

Multiplying out just the first row of  (corresponding to

(corresponding to  ), we see exactly the equation we want:

), we see exactly the equation we want:  .

.

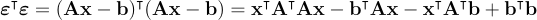

Now in our new nice matrix notation, we can express  as simply

as simply  , reformulating the least squares problem as

, reformulating the least squares problem as

Choose  to minimize

to minimize

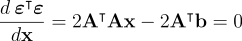

Whenever you see something telling you to find the minimum of an equation, of course your first thought is to take the derivative and set it equal to zero. There is another step to prove the extremum you found is a minimum, but who cares. We’ll just assume we will get a minimum doing this. (I think this is true because this equation is convex for some reason, but what do I know.) If you remember matrix derivates from second grade, we find

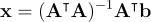

and solving for  , we obtain:

, we obtain:  .

.

Finally, as long as we have two unique points, we know  has a rank of two, and so

has a rank of two, and so  must have a rank of two (Is this even true??). Since

must have a rank of two (Is this even true??). Since  is a 2x2 matrix with a rank of 2, it must be invertible (Is this even true????). Thus, we multiply by the inverse and arrive at the classic equation:

is a 2x2 matrix with a rank of 2, it must be invertible (Is this even true????). Thus, we multiply by the inverse and arrive at the classic equation:

I know you’re think “Cool man. That was some nice math. BUT I’M TRYNNA HAVE MY BRAIN BOX BLOWN INTO SMITHEREENS.” Oh don’t worry my sweet baby baboon, this was just a warm up TO THE MOST CRAZY, BRAIN MELTING MATH EVER!!!!!! THIS SHIT BOUTA GET SO FREAAKING LIT!! Well ok. I mean granted, this is still just math, so it won’t be that incredibly cool. But like I personally got pretty excited when I was able to understand what follows (Shout out to Henry!), so hopefully you will find it mildly interesting.

The problem with all the above math is that it fails when you want to fit vertical lines. This is usually overlooked in discussions on linear regression because you will never have any meaningful trend in data be exactly vertical. You’ll get a vertical regression line only when you are trying to model something extremely dumb - like the relationship between gender and the likelihood of getting pregnant. However at work, I was trying to fit geometric lines in images, so vertical lines definitely were a possibility that needed to be accounted for. We can get around this problem with vertical lines by instead writing our line equation in homogeneous coordinates.

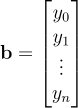

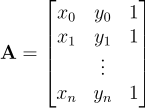

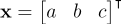

(Disclaimer: I don’t really understand homogeneus coordinates. All I know is you throw in an extra dimension, put an extra one on all your vectors, and things tend to work out). Now instead of defining a line with  , we have three variables

, we have three variables  that we are trying to estimate. Again, if we stack all points

that we are trying to estimate. Again, if we stack all points  into a matrix to work with all of them at once, we get the equation

into a matrix to work with all of them at once, we get the equation

, where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

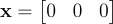

Ideally, all the errors are zero, so we can phrase the problem as “We want to find  that is in the nullspace of

that is in the nullspace of  .” Now the most trivial solution to this is to set

.” Now the most trivial solution to this is to set  , but that is meaningless. Instead we need to set constraints on

, but that is meaningless. Instead we need to set constraints on  . Since

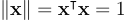

. Since  can be scaled to be any value, we force it to be a unit vector with length 1 because why not. Seems as good of a choice as any. In our optimization problem, we can represent this constraint via Lagrange multipliers. Again, we want to minimize

can be scaled to be any value, we force it to be a unit vector with length 1 because why not. Seems as good of a choice as any. In our optimization problem, we can represent this constraint via Lagrange multipliers. Again, we want to minimize  , but we add in this new constraint that

, but we add in this new constraint that  , giving us the problem

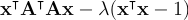

, giving us the problem

Choose  that minimizes

that minimizes

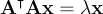

I have no idea why that extra term ensures we will get what we want, but it works. Again we take the derivative, set it equal to zero, and solve to get

Here we can see that  is an eigenvector of the matrix

is an eigenvector of the matrix  . Now since

. Now since  is a 3x3 matrix, we’ll have a maximum of three eigenvectors. Clearly we want the one with its eigenvalue as close to zero as possible because this will result in epsilon being as close to the zero vector as possible. And so we have arrived at our solution:

is a 3x3 matrix, we’ll have a maximum of three eigenvectors. Clearly we want the one with its eigenvalue as close to zero as possible because this will result in epsilon being as close to the zero vector as possible. And so we have arrived at our solution:

The line of best fit is the eigenvector of  associated with its smallest eigenvalue

associated with its smallest eigenvalue

This vector defines the parameters  for our line of best fit, and now there’s no risk of running into problems when the line is vertical. Additionally, you can think about this problem a different way. If we think of

for our line of best fit, and now there’s no risk of running into problems when the line is vertical. Additionally, you can think about this problem a different way. If we think of  as the covariance matrix of the points we are fitting, finding the line of best fit is equivalent to finding the axis through the data with the smallest “spread” or variance. This is exactly Principal Component Analysis. (It actually seems like we should be looking for the axis with the largest variance to define our line. However, remember in our line equation given above, we are looking for a vector

as the covariance matrix of the points we are fitting, finding the line of best fit is equivalent to finding the axis through the data with the smallest “spread” or variance. This is exactly Principal Component Analysis. (It actually seems like we should be looking for the axis with the largest variance to define our line. However, remember in our line equation given above, we are looking for a vector  that is ideally orthonormal to every point

that is ideally orthonormal to every point  . Thus, we are interested in finding the axis perpendicular to trend in the data, which corresponds to the axis with the smallest spread). We know from PCA that the axis with the smallest spread in the data will be the eigenvector of the covariance matrix associated with the smallest eigenvalue. This is the exact formula we found above through solving the least squares homogeneous equation. I think it is pretty cool that we can look at the problem from two different perspectives and arrive at the same solution. Go math!

. Thus, we are interested in finding the axis perpendicular to trend in the data, which corresponds to the axis with the smallest spread). We know from PCA that the axis with the smallest spread in the data will be the eigenvector of the covariance matrix associated with the smallest eigenvalue. This is the exact formula we found above through solving the least squares homogeneous equation. I think it is pretty cool that we can look at the problem from two different perspectives and arrive at the same solution. Go math!

Hopefully you found all of this interesting! I’m sorry for lying to you about how cool this blog post would be. But if we are being real, a blog post about linear regression needs a lot of help in order to go viral. If you hated this and feel betrayed and thought this was a big old waste of time, maybe you can get that anger out by sharing this post with someone you hate and want to waste their time. If you loved it, share this with everyone, and maybe shoot a heartfelt email to contact@elliottimhoff.com. Mainly, though, it is very important this post goes viral. This blog is all I have. I need you. I love you. I will find you if you don’t share this. But mostly I love you. Unless you don’t share this. Then you are dead to me. Stay safe out there people ❤️ ❤️ ❤️